Babesiosis is a tick-borne parasitic infection that has quietly moved from being a niche diagnosis to a clinically significant problem in the United States. Often compared to malaria because of its effect on red blood cells, babesiosis is caused primarily by Babesia microti, a microscopic parasite transmitted through the bite of the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis). In recent years, clinicians across the Northeast and Upper Midwest have reported a steady rise in confirmed cases, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimating more than 2,000 cases annually in the U.S., though experts agree the true number is likely higher due to underdiagnosis and asymptomatic infections.

From a clinical standpoint, babesiosis is a master of disguise. It can present like a mild viral illness or escalate into a life-threatening condition, especially in older adults, splenectomized patients, and individuals with compromised immune systems. Think of it as a quiet squatter in the bloodstream—sometimes barely noticeable, sometimes causing serious damage before anyone realizes it’s there.

Epidemiology

Babesiosis is geographically concentrated but expanding. The highest incidence is reported in states such as Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Warmer winters and longer tick seasons have contributed to a broader habitat for Ixodes ticks, increasing human exposure. In practical terms, this means babesiosis is no longer just a “coastal New England problem.”

Transmission occurs primarily through tick bites, but less commonly through blood transfusions. This transfusion-related route has prompted stricter blood screening protocols in endemic states, especially since donors may be asymptomatic. According to U.S. surveillance data, approximately 1–2% of cases are linked to transfusion transmission, a small but clinically important fraction ⧉.

Men are diagnosed slightly more often than women, and the median age of symptomatic patients is around 63 years. Children can be infected, but they are more likely to experience mild or asymptomatic disease. Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, notes that “the demographic shift toward older patients is one of the key reasons babesiosis has become more clinically relevant—it hits where resilience is already lower.”

Pathophysiology

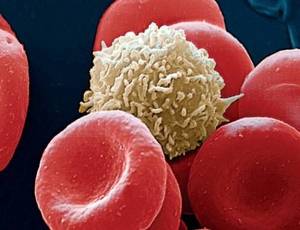

Once Babesia enters the bloodstream, it invades red blood cells and begins to replicate. As infected cells rupture, hemolytic anemia develops. This process is similar to popping balloons one by one—except the balloons are essential oxygen carriers. The result can be fatigue, shortness of breath, jaundice, and dark urine.

Unlike bacteria, Babesia parasites lack a cell wall, which explains why standard antibiotics like penicillins are ineffective. The immune system responds by activating macrophages and inflammatory pathways, sometimes tipping the balance toward excessive inflammation. In severe cases, this cascade can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), renal failure, or disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Parasitemia levels are a key determinant of severity. Mild cases often show less than 1% of red blood cells infected, while severe disease may exceed 10%. In splenectomized patients, the absence of splenic filtration allows parasitemia to rise rapidly—clinicians often describe this as “taking the brakes off the infection.”

Clinical Signs

The incubation period typically ranges from 1 to 4 weeks after a tick bite, but transfusion-related cases may present months later. Early symptoms are nonspecific and include fever (100–104°F / 37.8–40°C), chills, sweats, headache, myalgia, and profound fatigue. Many patients initially assume they have influenza or a summer viral illness.

As the disease progresses, signs of hemolysis become more apparent: pallor, jaundice, dark-colored urine, and splenomegaly (if the spleen is present). Laboratory findings often reveal anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzymes. In severe cases, hypotension and altered mental status may develop, signaling systemic involvement.

A notable clinical challenge is coinfection. Up to 20–30% of patients in endemic areas may also be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) or Anaplasma phagocytophilum. When symptoms linger despite standard Lyme therapy, babesiosis should be high on the differential diagnosis ⧉.

Diagnostics

Accurate diagnosis of babesiosis requires a combination of clinical suspicion and laboratory confirmation. The gold standard remains microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smears. This method allows direct visualization of intraerythrocytic parasites, including the classic “Maltese cross” formation. Accuracy: 8/10. Average cost in the U.S.: $40–$80.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing has become increasingly important, especially in cases with low-level parasitemia. PCR can detect Babesia DNA with high sensitivity and specificity. Accuracy: 9.5/10. Average cost: $150–$300. Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, recommends PCR “when clinical suspicion is high but smears are negative—this is where modern diagnostics really shine.”

Serologic testing using indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) assays helps identify past exposure but is less useful in acute decision-making. Accuracy: 6/10 for acute infection. Cost: $100–$200.

| Diagnostic Method | Accuracy (1–10) | Typical Cost (USD) | Key Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood smear | 8 | $40–$80 | Rapid initial diagnosis |

| PCR | 9.5 | $150–$300 | Low parasitemia, confirmation |

| IFA serology | 6 | $100–$200 | Epidemiology, past exposure |

Treatment Options

Antimicrobial Therapy

For mild to moderate babesiosis, the first-line regimen in the U.S. is atovaquone plus azithromycin. Atovaquone is typically dosed at 750 mg orally twice daily, while azithromycin ranges from 500–1,000 mg on day one followed by 250–500 mg daily. Treatment duration is 7–10 days. Effectiveness exceeds 90% in immunocompetent patients. Estimated medication cost: $250–$600 per course ⧉.

Severe cases require clindamycin plus quinine, often administered intravenously. While effective, quinine is associated with side effects such as tinnitus and hypoglycemia—patients often joke that “the cure announces itself loudly.”

Exchange Transfusion

In patients with parasitemia greater than 10%, severe hemolysis, or organ failure, red blood cell exchange transfusion is recommended. This procedure physically removes infected erythrocytes and replaces them with healthy donor cells. Effectiveness: rapid reduction in parasitemia (up to 90%). Average hospital cost: $8,000–$15,000.

Emerging Therapies

Research is ongoing into novel antiprotozoal agents and combination regimens, particularly for immunocompromised patients with relapsing disease. Experimental use of tafenoquine has shown promise in limited U.S. case series ⧉.

U.S. Case Stories

A 68-year-old male from coastal Connecticut presented with persistent fevers and fatigue in late August. Initially treated for presumed viral illness, he returned after two weeks with worsening anemia. Blood smear revealed 6% parasitemia. After atovaquone–azithromycin therapy, symptoms resolved within ten days. The patient later recalled removing a tick during a July gardening session—classic timing, classic miss.

In another case, a 54-year-old female from Wisconsin developed severe babesiosis following a blood transfusion after orthopedic surgery. She required ICU care and exchange transfusion but ultimately recovered. Cases like this underscore why blood donor screening has become a quiet but critical safeguard in endemic regions ⧉.

Prevention

Preventing babesiosis revolves around reducing tick exposure. Wearing long sleeves and pants, using EPA-approved tick repellents, and performing full-body tick checks after outdoor activities remain cornerstone strategies. Prompt tick removal within 24 hours significantly reduces transmission risk.

Landscape management—keeping grass short and removing leaf litter—can reduce tick density around homes. While no human vaccine exists, ongoing research mirrors advances made in veterinary babesiosis prevention.

Editorial Advice

From an editorial standpoint, babesiosis deserves more clinical attention than it often receives. Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, emphasizes that “persistent fever and anemia during tick season should never be brushed off—early testing saves lives and resources.” Clinicians are encouraged to think beyond Lyme disease and consider babesiosis early, especially in older adults.

For patients, awareness is key. Babesiosis is not rare anymore—it’s just good at hiding. A little vigilance goes a long way, and when caught early, outcomes are overwhelmingly positive. In medicine, timing isn’t everything—but here, it’s pretty close.