Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) is one of those laboratory numbers clinicians watch like a hawk. It may look like just another value on a complete blood count (CBC), but in reality, ANC acts as an early-warning radar for the immune system. Neutrophils are the body’s first responders—think of them as firefighters rushing toward infection before anyone else even smells smoke. ANC tells clinicians exactly how many of these cells are circulating in the blood at any given moment.

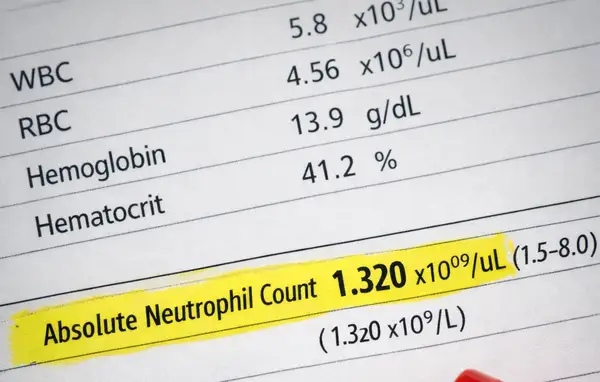

ANC is calculated using a simple formula based on the total white blood cell (WBC) count and the percentage of neutrophils (including bands). In adults, a normal ANC typically ranges from 1,500 to 8,000 cells/µL (1.5–8.0 ×10⁹/L). Values below this range raise clinical eyebrows, while very low levels may trigger immediate action. In the U.S., ANC is routinely used in oncology, hematology, infectious disease, and emergency medicine.

From a population perspective, mild transient reductions in ANC are relatively common and often benign. However, persistent or severe neutropenia significantly increases the risk of serious bacterial and fungal infections. According to U.S. hospital data, patients with ANC below 500 cells/µL have up to a 7-fold higher risk of life‑threatening infections compared with immunocompetent individuals ⧉.

What ANC Measures

ANC specifically measures the absolute number of neutrophils in the bloodstream, not their function or quality. This distinction matters. A patient may have “normal-looking” neutrophils that are numerically insufficient, leaving the immune defense understaffed.

The calculation is:

ANC = WBC × (% neutrophils + % bands) / 100

For example, a WBC of 4,000 cells/µL with 50% neutrophils results in an ANC of 2,000 cells/µL—well within normal limits. Simple math, big implications.

Clinically, ANC is categorized as:

- Mild neutropenia: 1,000–1,500 cells/µL (1.0–1.5 ×10⁹/L)

- Moderate neutropenia: 500–1,000 cells/µL (0.5–1.0 ×10⁹/L)

- Severe neutropenia: <500 cells/µL (<0.5 ×10⁹/L)

Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, emphasizes that clinicians should always interpret ANC dynamically, not as a single snapshot. Trends over days or weeks often tell a much more reliable story than one isolated value.

Causes of Abnormal ANC

Abnormal ANC values can result from decreased production, increased destruction, or abnormal distribution of neutrophils. In the U.S., the most common causes differ depending on clinical setting.

Low ANC (Neutropenia) may be caused by:

- Bone marrow suppression (chemotherapy, radiation)

- Viral infections (influenza, EBV)

- Autoimmune disorders

- Nutritional deficiencies (vitamin B12, folate)

- Congenital neutropenia syndromes

High ANC (Neutrophilia) is often associated with:

- Acute bacterial infections

- Systemic inflammation

- Physical stress or trauma

- Corticosteroid use

Epidemiological data suggest that chemotherapy-induced neutropenia affects 40–60% of U.S. cancer patients, making ANC monitoring non-negotiable in oncology practice ⧉.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory diagnostics play a central role in evaluating Absolute Neutrophil Count. The methods below are routinely used in U.S. clinical practice and often complement each other to provide a complete picture of neutrophil quantity and morphology.

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

The CBC with differential is the cornerstone diagnostic test for ANC assessment.

- How it’s done: Venous blood draw (5–10 mL / ~1–2 teaspoons or 5–10 mL)

- Accuracy: 9/10

- Average U.S. cost: $20–$50

Modern automated hematology analyzers (e.g., Sysmex XN-Series, Beckman Coulter DxH) provide highly reproducible results within minutes. These systems use flow cytometry and impedance-based technologies to distinguish neutrophils from other leukocyte populations.

Peripheral Blood Smear

Used when automated results are questionable or severe abnormalities are detected.

- How it’s done: Manual microscopic examination of stained blood cells

- Accuracy: 8/10 (operator-dependent)

- Average cost: $30–$70

This method allows direct visualization of neutrophil size, granulation, and nuclear segmentation, which can reveal bone marrow stress or inherited abnormalities.

Bone Marrow Examination

Reserved for unexplained or persistent neutropenia.

- How it’s done: Aspiration and biopsy from the posterior iliac crest (≈0.5–1 inch / 1–2.5 cm needle depth)

- Accuracy: 10/10

- Average cost: $1,500–$3,000

Bone marrow evaluation distinguishes reduced neutrophil production from peripheral destruction and remains the gold standard when serious hematologic disease is suspected.

Modern Treatment Approaches

Treatment depends entirely on severity, cause, and clinical context.

Observation and Monitoring

For mild, asymptomatic neutropenia, no immediate treatment is often required.

- Effectiveness: High in benign cases

- Cost: Minimal

Colony-Stimulating Factors

Medications such as filgrastim (Neupogen) and pegfilgrastim (Neulasta) are widely used in the U.S.

- Mechanism: Stimulate bone marrow neutrophil production

- Effectiveness: 8.5/10

- Cost: $300–$6,000 per dose

Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, notes that growth factors have dramatically reduced hospitalization rates in chemotherapy patients over the past decade.

Treating Underlying Causes

- Vitamin B12 or folate replacement

- Adjusting or discontinuing causative medications

- Managing autoimmune activity with targeted therapies

Real U.S. Clinical Cases

A 62-year-old woman from Ohio had been navigating breast cancer treatment for several months when fatigue started to feel different — heavier, more persistent. She initially blamed it on chemotherapy, but when a low-grade fever appeared, her oncology team ordered an urgent CBC. The results showed her ANC had fallen to 420 cells/µL. What followed was a tense but controlled period of close monitoring, growth factor support with pegfilgrastim, and careful adjustment of her treatment schedule. Thanks to early detection and rapid intervention, she avoided hospitalization and was able to continue cancer therapy with confidence rather than fear.

By contrast, a 34-year-old man from California encountered the concept of ANC almost by accident. During a routine annual physical, his blood work repeatedly showed mild neutropenia, despite the fact that he felt perfectly healthy. Curious and increasingly concerned after several follow-up tests, he was referred to a hematologist. Further evaluation revealed benign ethnic neutropenia — a normal genetic variant rather than a disease. For him, the journey ended not with medication, but with reassurance and a clearer understanding of his own biology ⧉⧉.

Prognosis

The outlook for patients with abnormal ANC varies widely. Transient neutropenia often resolves within days to weeks, while chronic severe cases require long-term monitoring. Advances in diagnostics and biologic therapies have significantly improved outcomes. Hospital mortality related to neutropenic complications in the U.S. has declined by over 30% since 2005 ⧉.

Editorial Advice

Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, advises patients to view ANC not as a frightening number but as a valuable communication tool between the immune system and clinicians. Regular monitoring, prompt evaluation of trends, and individualized management strategies are key.

Editorially, the most practical advice is simple: never ignore persistent abnormalities, but also avoid panic over isolated results. In modern American medicine, ANC is less about alarm and more about anticipation—catching problems early, staying one step ahead, and letting science do the heavy lifting ⧉.