Every expectant mother knows that pregnancy is a journey filled with both joy and challenges. As the due date approaches, one of the most common and sometimes confusing experiences is body pain before labor. Is it just normal pregnancy discomfort, or is the body signaling that labor is right around the corner? For many women, understanding the difference can mean less anxiety and a smoother transition into childbirth.

What Does Body Pain Before Labor Actually Mean?

Body pain before labor is the body’s natural way of preparing for childbirth. In late pregnancy, the ligaments, muscles, and pelvic joints begin to loosen under the influence of hormones like relaxin and oxytocin. This creates increased mobility in the pelvis but also contributes to soreness, stiffness, and discomfort. Many women describe it as a deep ache in the lower back or pelvis that comes and goes unpredictably. Unlike general pregnancy discomfort, pain associated with the approach of labor tends to be more rhythmic and concentrated.

Statistically, about 70% of American women report experiencing back or pelvic pain in the last weeks of pregnancy, with 50% linking it directly to early labor signs. Studies show that the intensity of this pain can vary significantly, with some women rating it as mild discomfort while others experience pain severe enough to disrupt sleep and daily activities. For example, a 34-year-old woman from California reported persistent lower back pain for three days before her labor started naturally — a common narrative among U.S. mothers.

Reyus Mammadli, a medical consultant, emphasizes that “not all pain before labor is dangerous, but learning to interpret the type, location, and timing of pain is key to knowing when labor is imminent.” His view highlights the importance of awareness, which can help expectant mothers respond appropriately without unnecessary stress.

Which Types of Body Pain Are Most Common Before Labor?

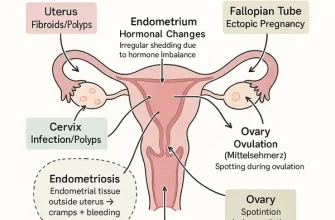

Expectant mothers often wonder if the aches they feel are ordinary or a labor signal. The most frequently reported types of pre-labor pain include:

- Lower back pain: Usually a deep, dull ache that worsens as the uterus contracts and presses against the spine. About 60% of pregnant women in the U.S. report this symptom in the final trimester.

- Pelvic pressure and cramping: As the baby “drops” into the birth canal (a process called lightening), the increased pressure can cause sharp pains in the pelvic joints. This is especially common in women having their first baby.

- Abdominal tightening: Often mistaken for digestive discomfort, these are usually Braxton Hicks contractions — irregular and less painful than real labor contractions.

- Leg and thigh pain: Caused by nerve compression, especially the sciatic nerve, due to the baby’s position.

Take, for instance, a 29-year-old mother from New York City who experienced shooting pains down her thighs two days before her water broke. While initially confused, her doctor confirmed it was pressure on the sciatic nerve from the baby’s engagement.

These examples underscore how body pain varies but often shares a common theme: the body is adjusting for the imminent delivery. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ⧉, monitoring how pain evolves — in frequency and intensity — can help distinguish early labor from normal discomfort.

How to Tell If It’s Labor or Just Discomfort?

This is the million-dollar question for many moms-to-be. The primary difference between labor and regular pregnancy discomfort lies in consistency and progression. Braxton Hicks contractions, often referred to as “false labor,” are irregular, unpredictable, and usually stop with rest or hydration. In contrast, real labor contractions become stronger, longer, and closer together with time.

Comparison Table: Braxton Hicks vs. Real Contractions

| Feature | Braxton Hicks | Real Labor |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Irregular | Regular, increasing in frequency |

| Duration | 30 seconds or less | 30–70 seconds |

| Intensity | Mild, does not worsen | Intensifies over time |

| Relief | Improves with hydration/rest | No relief from position changes |

A case from Florida highlights this difference: a 31-year-old woman initially dismissed her abdominal tightening as Braxton Hicks. However, after tracking the contractions with an app, she noticed they were becoming more frequent and painful, signaling the real deal.

Reyus Mammadli notes that “technology can be a big help — even a simple smartphone app can differentiate false alarms from true labor by charting contraction patterns.” That’s one way modern tools make this experience less intimidating.

Modern Diagnostic Approaches to Pain Before Labor

Medical professionals use a variety of diagnostic methods to evaluate whether body pain indicates imminent labor. Beyond cost and accuracy, it is important to know how these tests are performed, what to expect during the process, and how safe and comfortable they are:

- Ultrasound: This test uses high-frequency sound waves to create images of the uterus and baby. A technician applies gel to the abdomen and moves a transducer over the skin. The process is painless, takes about 15–30 minutes, and results are available immediately. Safety is high, with no radiation involved, making it one of the most commonly used diagnostic tools. Accuracy: 7/10. Average cost in the U.S.: $200–$500.

- Cardiotocography (CTG): CTG monitors uterine contractions and fetal heart rate. Elastic belts with sensors are placed around the mother’s abdomen. The procedure is non-invasive and typically lasts 20–40 minutes. Mothers may feel mild pressure from the belts but no pain. Results are available in real time, and the test is considered very safe for both mother and baby. Accuracy: 8/10. Average cost: $150–$250.

- Cervical examination: Conducted manually by an obstetrician or midwife wearing sterile gloves. The provider gently inserts fingers into the vagina to assess cervical dilation and effacement. The exam may cause brief discomfort or pressure but is usually tolerable. Results are immediate. Safety is high, although repeated exams should be minimized to reduce infection risk. Accuracy: 9/10 when combined with contraction monitoring. Cost: usually included in prenatal care visits.

- Fetal fibronectin test: A cotton swab is placed in the vagina near the cervix to collect a sample, similar to a Pap test. The procedure takes only a few minutes and may cause mild discomfort but no pain. Results are usually available within 24 hours. This test is safe and carries minimal risk. Accuracy: 6/10. Cost: $250–$450.

Recent innovations include AI-assisted CTG interpretation, which increases accuracy to 9/10 by reducing human error. Hospitals like Mount Sinai in New York have begun integrating these technologies into routine obstetric care ⧉. These advances not only improve safety but also make diagnostics faster and more reassuring for mothers.

This diagnostic arsenal not only reassures mothers but also reduces unnecessary hospital admissions due to false alarms.

Are There Risk Factors That Make Pain Worse?

Certain conditions can intensify pre-labor body pain:

- High BMI: Extra weight increases strain on joints and ligaments.

- Maternal age over 35: Older mothers report more severe pelvic and back pain, according to NIH studies ⧉.

- Previous back injuries or chronic pain conditions: Exacerbate pregnancy discomfort.

- Multiple pregnancies: Carrying twins or more significantly heightens pelvic pressure.

For instance, a 38-year-old woman in Texas expecting twins reported that her pelvic pain made walking nearly impossible in the final week before labor. Her obstetrician explained that the combination of maternal age and twin pregnancy created a perfect storm of discomfort.

Reyus Mammadli advises that women with these risk factors should maintain closer communication with their healthcare providers and not hesitate to seek early evaluation if pain becomes unmanageable.

Safe Ways to Manage Pain Before Labor

Managing pre-labor pain safely is crucial, especially since many medications can affect both mother and baby. The goal is not only to ease discomfort but to do so in a way that avoids complications. Here are evidence-based approaches with practical details:

- Medication: Acetaminophen (paracetamol, branded as Tylenol in the U.S.) is considered the safest over-the-counter option for mild to moderate pain. The recommended dose is typically 500–650 mg every 4–6 hours as needed, not exceeding 3,000 mg in 24 hours unless directed by a physician. It works by blocking pain signals in the brain without affecting uterine contractions. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen are generally avoided in the third trimester due to potential risks to the fetus.

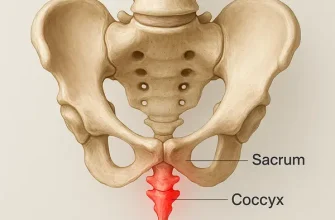

- Supportive devices: Maternity belts and pelvic support bands redistribute abdominal weight, reducing strain on the lower back and pelvis. They function by stabilizing the sacroiliac joints and improving posture. To be effective, they should be worn snugly but not tightly, ideally for a few hours at a time. Overuse (more than 8–10 hours daily) can lead to muscle weakening, so alternating with gentle movement is recommended.

- TENS therapy (Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation): This method delivers mild electrical impulses through skin electrodes placed on the lower back. These impulses interfere with pain signals and stimulate endorphin release. Sessions typically last 30–60 minutes, and many U.S. hospitals provide TENS units for supervised use. Pregnant women should avoid placing electrodes on the abdomen and should seek instruction from a physical therapist or nurse before starting.

- Warm compresses or showers: Applying a warm (not hot) compress to the lower back or taking a warm shower relaxes muscles and increases blood flow. The water temperature should not exceed 100°F (38°C). A 10–15 minute shower, once or twice daily, is usually safe. Red flags include dizziness, overheating, or uterine contractions that become unusually painful — in such cases, the method should be stopped immediately.

- Physical therapy: Certified prenatal physical therapists use targeted exercises to strengthen core and pelvic floor muscles, improving mobility and reducing pain. Techniques include gentle stretches, posture training, and breathing exercises. Sessions usually last 30–45 minutes, and many clinics in the U.S. now offer telehealth consultations for added convenience.

One innovation gaining traction is the use of cooling maternity belts, which combine mechanical support with localized cold therapy to reduce inflammation. These products, available at retailers like Target and Amazon, are backed by preliminary clinical studies ⧉. They are typically used for 20 minutes at a time and should not be applied directly to bare skin to avoid cold burns.

When used properly, these methods can significantly improve comfort in the final weeks of pregnancy without harming mother or baby. However, as Reyus Mammadli emphasizes, “Every expectant mother should consult her provider before starting any new pain relief technique, even if it seems harmless.”

When Should You See a Doctor Immediately?

While many aches are normal, certain red flags demand urgent attention. The key is not just the symptom itself but how it presents:

- Vaginal bleeding: Light spotting, especially after a cervical check, may be harmless. But heavy bleeding (soaking a pad in an hour or passing clots), bleeding that persists beyond a few minutes, or bleeding combined with pain can signal placental problems and requires urgent evaluation.

- Severe, sudden abdominal pain: Mild cramps that come and go can be part of labor. However, pain that is constant, sharp, or does not ease between contractions can indicate complications such as placental abruption. If this pain is accompanied by back pain or bleeding, it becomes an emergency.

- Noticeable decrease in fetal movement: Babies sometimes have quiet periods, but if the baby moves significantly less than usual over several hours (especially after eating or resting), this should be treated seriously. A common guide: fewer than 10 movements in two hours in late pregnancy is a red flag.

- Fever combined with body pain: A mild rise in temperature may occur for many reasons, but a fever of 100.4°F (38°C) or higher, especially with chills, uterine tenderness, or foul-smelling discharge, may point to infection and requires immediate medical attention.

A 26-year-old woman in Chicago ignored persistent severe cramps with moderate bleeding, assuming it was pre-labor pain. Later, she was diagnosed with placental abruption — a serious complication. Early hospital evaluation could have prevented the escalation.

As Reyus Mammadli puts it: “When in doubt, check it out. It’s better to have a doctor confirm a false alarm than to miss a serious complication.”

Editorial Advice

Body pain before labor can be confusing, but it is also the body’s way of signaling readiness for one of life’s most important events. Expectant mothers should learn to distinguish between ordinary discomfort, Braxton Hicks contractions, and true labor. Modern technology, from smartphone apps to AI-assisted diagnostics, is making this process easier and more reliable.

Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, recommends that women keep a pain diary, note contraction patterns, and maintain open communication with their obstetric care team. He stresses that “trusting your body while using modern medical tools gives the best outcome.”

Final tip: don’t underestimate the power of preparation. Knowing when pain is normal and when it’s a warning sign allows expectant mothers to approach labor with confidence rather than fear.